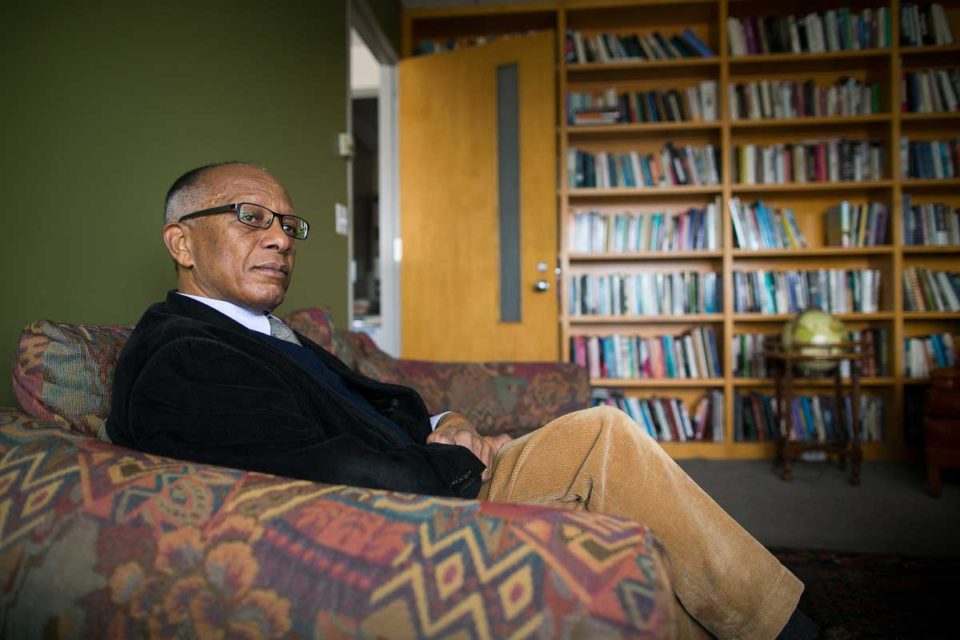

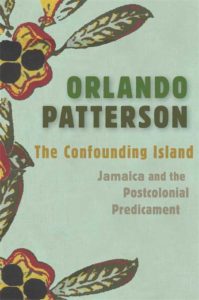

Orlando Patterson’s ‘return’ to Jamaica is not a physical one (although he visits his homeland at least twice a year) but refers to the title of a forthcoming book, The Confounding Island: Jamaica and the Postcolonial Predicament, his first about Jamaica since the publication of his last work Die the Long Day, a fictional work about Jamaican slave society almost half a century ago.

Patterson left Jamaica around 1970 for Harvard University in the US where he has remained ever since and is now the John Cowles Professor of Sociology and one of the Academy’s ‘big thinkers’. He has earned a national presence in the US as a public intellectual noted for his op-ed essays in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time and Newsweek magazines and has appeared on the PBS News Hour and Hardball with Chris Matthews on MSNBC.

Patterson left Jamaica around 1970 for Harvard University in the US where he has remained ever since and is now the John Cowles Professor of Sociology and one of the Academy’s ‘big thinkers’. He has earned a national presence in the US as a public intellectual noted for his op-ed essays in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time and Newsweek magazines and has appeared on the PBS News Hour and Hardball with Chris Matthews on MSNBC.

During one of his recent visits to Jamaica we caught up with Patterson to talk about The Confounding Island, as well as a range of issues on which he has attracted controversy by his challenge of accepted dogma. In the new work scheduled for release this coming November, Patterson investigates the failure of Jamaica’s post-colonial democracy, exploring why the country has been unable to achieve broad economic growth and why its free elections and stable governments have been unable to address violence and poverty.

Among the searching questions he poses and seeks to answer is whether it is good policies or good institutions that influence development. Unlike fellow Jamaican economist Peter Blair Henry, Dean of New York University’s Stern School of Business, who has come down on the side of ‘policies’ Patterson belongs to the school of thought that places emphasis on ‘ institutions’. Countries like Jamaica, says Patterson, have long suffered from what MIT economist Daron Acemoglu calls, the ‘fallacy of ignorance’ perpetuated by multi-lateral institutions like the World Bank, who operate on the premise that the lack of development is a matter of not having the right policies. He argues that no matter how good the policies are, without the institutional framework a country will not achieve its development goals. However for Patterson it is not enough to have good institutions, but playing the institutional game the right way – meaning having a long tradition and know-how to run those institutions. Like Henry he compares the steady economic progress made by Barbados which had similar institutions as Jamaica at the time of Independence and who concludes that it must be the policies in Barbados that makes the difference in per capita earnings and its ranking on the Human Development Index.

Not so, says Patterson; the difference is that Barbados acquired the institutional knowledge soon after the ending of slavery by using its black citizens as bureaucrats, policemen, artisans etc. and generally did a better job at educating the people so that when independence came they knew how to run a democracy. Jamaica’s history was very different. It not only abandoned its parliamentary system and opted for rule by the Colonial Office for close to a hundred years, but had a largely absent elite. True, Jamaica did have black civil servants and a coloured middle class but nowhere as developed as in Barbados. A 1972 study by the late Gladstone Mills, then Professor of Public Administration at the University of the West Indies came to the startling conclusion that Jamaica had an ineffective civil service because up to the time of independence all major decisions were still being made by the colonialists. In other words, they had not learned how to play the institutional game.

To this, Patterson adds the cultural factor – a major pillar of his philosophy. The level of acculturation to British ways was considerably weaker in Jamaica because of a strong Afro-Jamaican culture in which the peasants were involved and which explains Jamaica’s cultural vitality. The downside is endemic violence, class conflict and corruption, hence the inability of the country to move forward.

Patterson is no ‘gloomy Cassandra’. He was careful not to use the imperative form of the word ‘confound’ to describe the Jamaican predicament. At the same time he acknowledges that there are significant hopeful signs and cause for optimism that at last Jamaica could be turning the corner with positive economic indicators. This he attributes in part to ‘good politics’ the third side of the triangle made up of ‘good policies’ and ‘good institutions’. In the current case of Jamaica, the good politics can be seen in the apparent consensus between Government and the Opposition to continue the policy of fiscal discipline initiated by the previous government. Jamaica’s current Minister of Finance Nigel Clarke concurs, adding that having reached the bottom of the pit and with nowhere else to go, the country has no other option but to remain on the path of fiscal discipline, for which civil society support is a crucial requirement.

Densil Williams, Professor of International Business at the University of the West Indies in an address to the Association of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators earlier this month on organizational change, said for change to be effective it has to be visible and lived. The answer to Patterson’s query as to what explains the change and why Jamaicans now appear to believe that economic progress is actually at hand may well be in the many cranes and construction sites, roads and other infrastructural works that are visibly in progress all over the country.

***************

Patterson’s reputation as a public intellectual has been built on his work as a historical-comparative sociologist writing extensively on race relations especially slavery and Freedom. Slavery and Social Death was the landmark study that brought him to international attention but it was Freedom in the Making of Western Culture, which won the 1991 National Book Award for non-fiction that earned him the accolade of being ranked among sociology’s ‘big thinkers’. However, it was his first academic book, The Sociology of Slavery, an historical account and analysis of Jamaican slavery published in 1967 that stamped him as one to watch in the future. It came out of his PhD thesis awarded in 1965 which immediately catapulted him on to the faculty of the world-famous London School of Economics (LSE).

Patterson’s reputation as a public intellectual has been built on his work as a historical-comparative sociologist writing extensively on race relations especially slavery and Freedom. Slavery and Social Death was the landmark study that brought him to international attention but it was Freedom in the Making of Western Culture, which won the 1991 National Book Award for non-fiction that earned him the accolade of being ranked among sociology’s ‘big thinkers’. However, it was his first academic book, The Sociology of Slavery, an historical account and analysis of Jamaican slavery published in 1967 that stamped him as one to watch in the future. It came out of his PhD thesis awarded in 1965 which immediately catapulted him on to the faculty of the world-famous London School of Economics (LSE).

Although The Sociology of Slavery remains the classic study of Jamaican slave society, Patterson discerns attempts by some Caribbean historians to sideline the work and to deliberately neglect its contribution. He singles out for special criticism, Kamau Brathwaite’s focus on the creolization idea, describing it as a ‘bourgeois gimmick’ which normalizes slavery as not being all bad. He is equally critical of Barry Higman’s reliance on cliometrics to make the case that the destruction of the family did not take place under slavery and to characterize slave society as just ‘another kind of society’. He chastises those historians for focusing on ‘Great Houses’ rather than on the hell-like experience of the enslaved and the 200 years of genocide of black people by white slave masters.

Patterson might yet have the last laugh as historians making the case for Reparations are now focusing on the genocidal aspects of slavery as crimes against humanity. The bases on which reparations claims are being made also vindicate the central core of his arguments over the past 40 or so years that the study of culture which is a distillation of the past involving learned behaviours, social ills, and other non-biological inheritances are as vital to the understanding of contemporary social phenomena as prevailing structures like institutions, distribution of wealth, education, housing, jobs etc.

Patterson’s full return to a focus on Jamaica may well be on the cards in the not too distant future. For now, and in the immediate future he is bent on wrapping up a number of academic projects but looking down the road he could move back into fiction if the literary muse is still there.

In Part two, Patterson talks about his choice of an academic career over being a fiction writer; US immigration policies and the ‘Windrush’ atrocity as social death for blacks in America and Britain; Trumpism and the ascendancy of right-wing politics in America and prospects for the 2020 presidential elections.